Author: eric

Janus

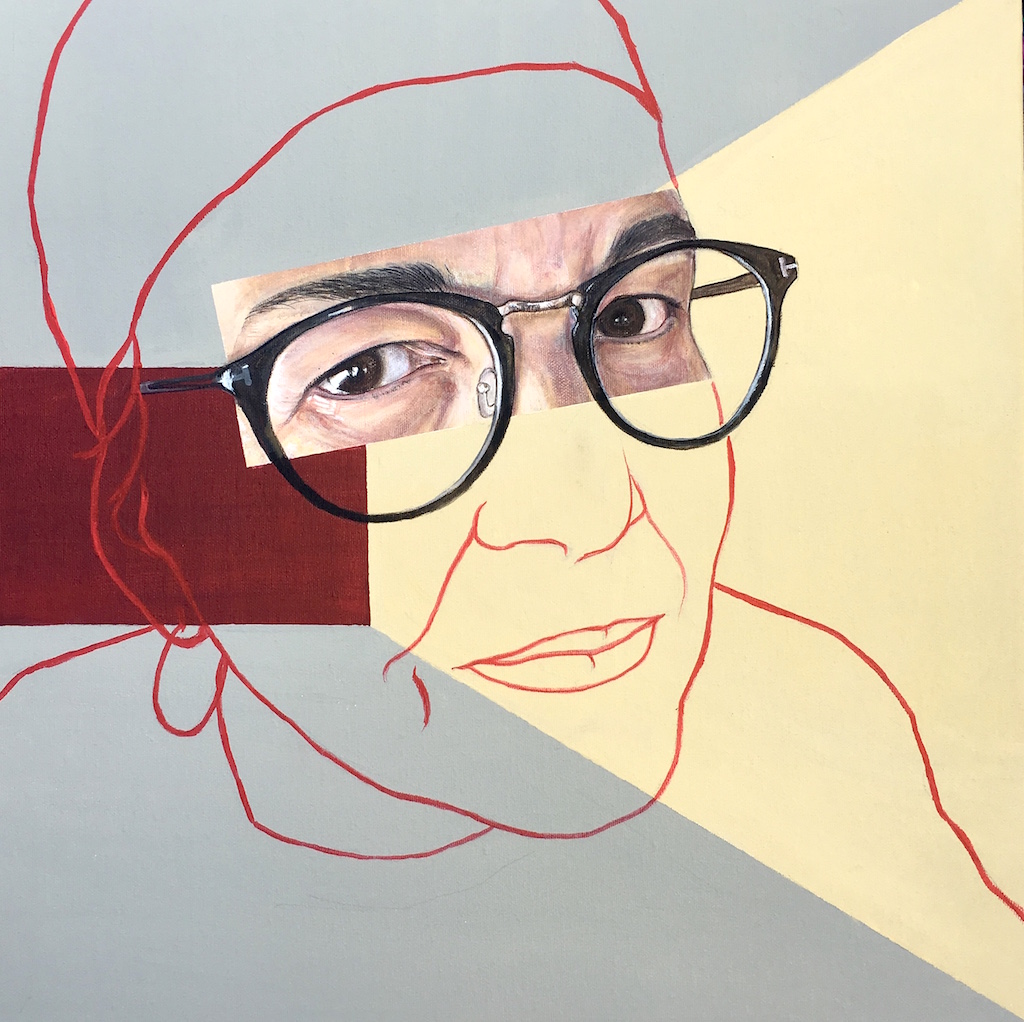

Cephaloself

The Centaur

Eye’ll Be Seeing You

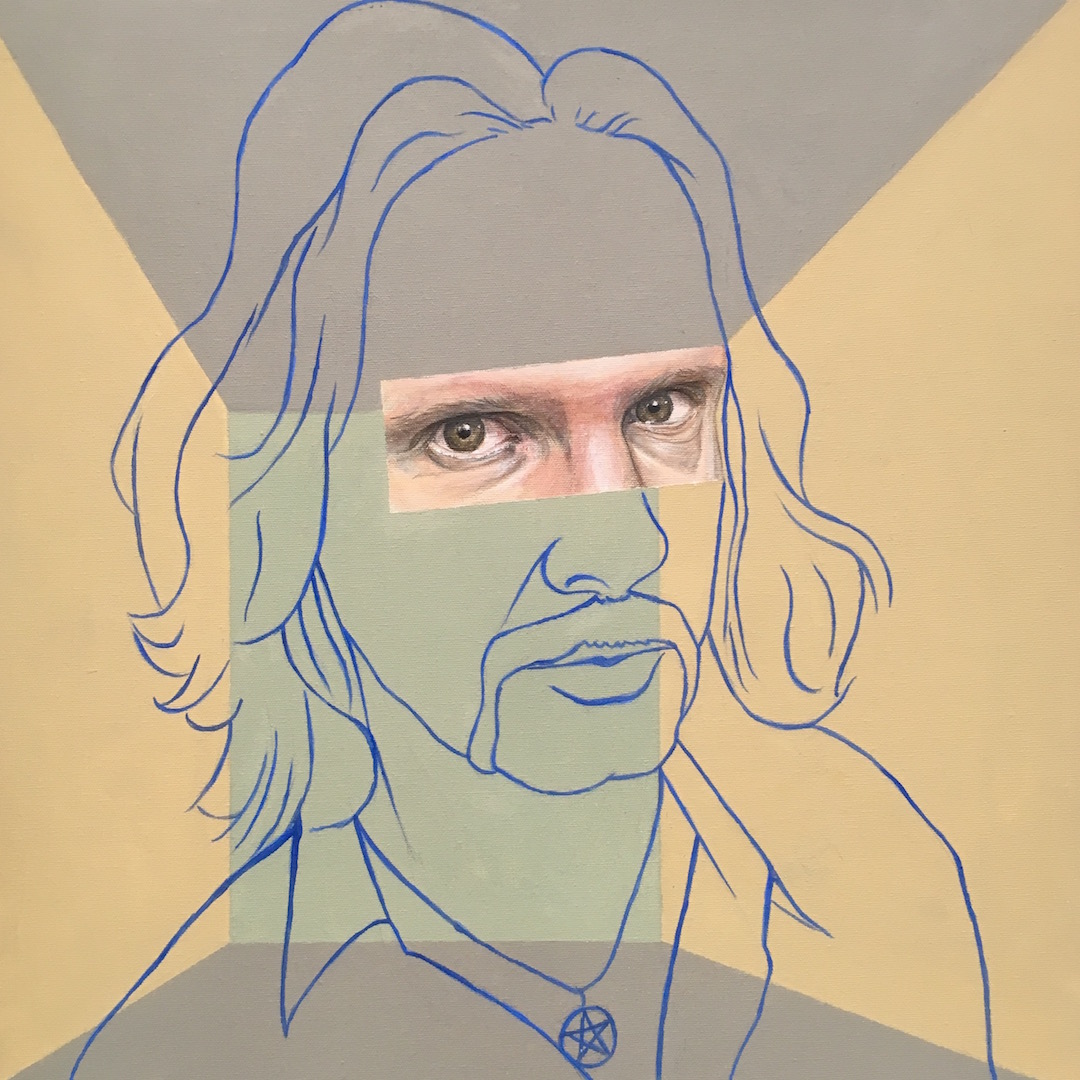

The Antipope

Lucky Jim

The Other Eric

Private Language

portrait of Ludwig Wittgenstein – more details on shardcore.org

Orange Norma Jean

The Minotaur

The Wrong Child

A Gentleman’s Wager

Self

Nietzsche and the horse II

Edie

Tibs

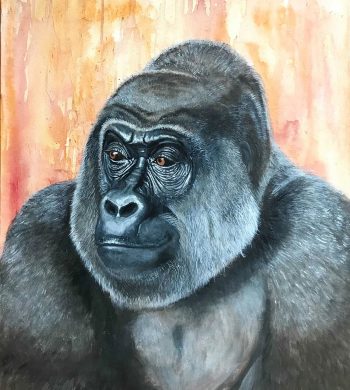

King Bear

Ben

Melinda